The relationship between intestinal microbiota and the innate immune system: The role of ImmunoWall® in this process

Liliana Borges and Melina Bonato (R&D Brazil, ICC Brazil)

For a few years, we have been receiving advice from international health organizations about the use of antibiotics in the animal production industry. The World Health Organization (WHO) warned that a lack of effective antibiotics was as serious a threat to security as a deadly disease outbreak. We should focus our attention on a set of measures which promote safe animal growth and mainly act in the prevention of diseases.

Many studies prove that beyond antibiotics’ immediate impact on microbiota, these types of medicines also affect the genetic expression, protein activity, and general metabolism of intestinal microbiota. As well as increasing the immediate risk of infection, the microbial changes caused also have long terms effects on the basic immune system.

Animals’ intestinal microbiota plays an important role in regulating their immune systems, since it not only modulates various physiological, nutritional, metabolic and disease-fighting processes, but can also alter the physiopathology of illnesses, conferring resistance, or promote enteric parasitical infections. Natural intestinal bacteria act as molecular adjuvants which provide indirect immunostimulation, helping the organism defend itself against infections.

Broilers have a large quantity of lymphoid tissue and immune system cells in their intestinal mucosa, called the GALT (gut-associated lymphoid tissue), which in turn constitutes the MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue). The GALT is constantly exposed to food antigens, microbiota, and pathogens (DALLOUL & LILLEHOJ, 2006), and needs to identify components which are present in the intestinal lumen and which could present a possible threat to the animal. The immune system’s first line of defense is composed of phagocytic cells (macrophages, heterophiles, dendritic cells and natural killer cells), which have Toll-type receptors on their surface. These receptors recognize microbial standards and induce an immediate innate immune response. After this activation and phagocytosis, the phagocyte (antigen-presenting cell – “APC”) presents a processed fragment of the antigen and a chain reaction is initiated against it. The innate immune system’s recognition of pathogens first triggers immediate innate defenses and, subsequently, the activation of the adaptive immune response (LEE & IWASAKI, 2007).

It is important to emphasize that this series of responses of the innate immune system requires several nutrients, especially metabolic energy, since it is a nonspecific and pro-inflammatory response, but necessary to control the proliferation, invasion, and damage caused by the antigen in the animal organism. However, a prolonged pro-inflammatory response may lead to secondary diseases, immunosuppression, maintenance of immune homeostasis, intestinal dysbiosis, and finally, decline in performance and mortality.

A correct program of measures, including balanced nutrition, vaccination, reduction of stress factors, good management and animal well-being practices, can considerably decrease the occurrence of immunosuppression. Adding dietary additives, which act in the modulation of the innate immune system and microbiota, improves the defense response against potential challenges.

The ImmunoWall®, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is derived from the process of sugar cane fermentation in ethanol production, and is made up of around 35% β-glucans (1,3 and 1,6) and 20% Mannan-Oligosaccharides (MOS). β-glucans are recognized for their phagocytic cells (PETRAVIĆ-TOMINAC et al., 2010), encouraging them to produce cytokines which will initiate a chain reaction to induce immunomodulation and enhance the responsiveness of the innate immune system. On the other hand, MOS are able to agglutinate type-1 fimbriae pathogens and various strains of Salmonella and Escherichia coli.

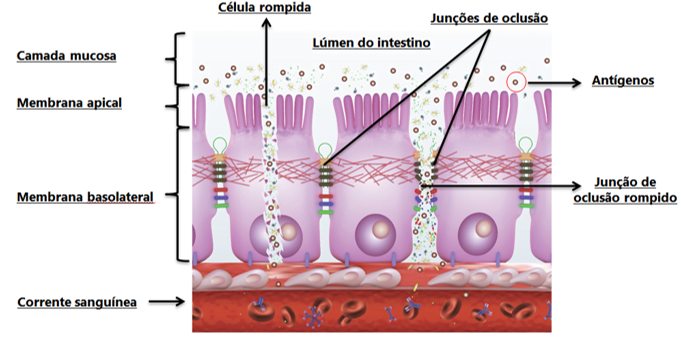

A recent study conducted by Beirão et al. (2018), in which broilers received ImmunoWall® supplements (0.5 kg/MT) and were infected with Salmonella Enteritidis [SE] (via an oral dosage of 108 CFU per broiler) at two days of age, showed that from four to eight days of age (two and six days post-infection, respectively), ImmunoWall® reduced the passage of the marker (Dextran-FITC, 3-5 kD) into the challenged broilers’ blood stream. These results show a significant improvement in intestinal integrity and permeability, since SE is a bacterium capable of sticking to the mucosa through its fimbriae, producing toxins and causing damage to tight junctions and enterocytes, invading them and translocating them into the blood stream and other internal organs and tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dynamic of antigens’ damage process to the tight junctions.

These results can be explained through the quantification of circulating cells analyzed in blood collected from these broilers. It is important to note that during the normal dynamics of an infection, a mobilization of leukocytes from the blood to the intestine occurs; however, if the animal displays another type of infection, the reduction of total circulating leukocytes may impair the response to the attack on this second antigen/area. This is especially dangerous when the rate of total leukocytes in the blood is very low (leukopenia). In the analysis of the aforementioned study, the infected group which received ImmunoWall® supplements showed less leukocyte mobilization from the blood to the intestine at 14 days of age. However, when this immune system is subdivided and the different cells are analyzed, the animals from this group showed more APC’s, suppressor monocytes (which prevent an unrestrained immune response), and auxiliary T lymphocytes (CD4, which secrete interleukins and stimulate the multiplication of cells that can attack the antigen), than the group of challenged and non-treated animals. The group which received ImmunoWall® supplements without being infected presented intermediary responses (between infected and non-infected control) to the analyzed cells mentioned above, as well as to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8), which are important to prevent and control Salmonella infection, since they are able to invade monocytes and thus translocate to the liver and other organs.

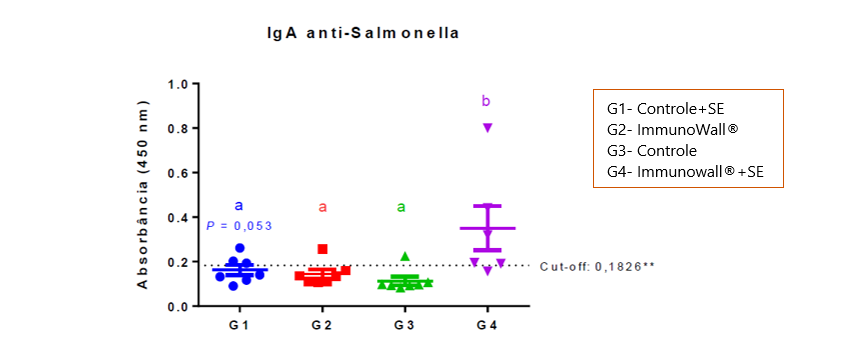

The graph 1 below shows that using ImmunoWall® supplements resulted in the biggest production of IgA anti-Salmonella at 14 days of age. This shows that the specific response of the immune system was faster and stronger, consuming less energy and nutrients, since the inflammatory response appeared to be shorter.

Graph 1. Relative quantification of IgA in the reagent serum against the bacteria’s LPS. Cut-off line is shown. Statistic relevancy is indicated by the letters above each group. ANOVA test with post-hoc Tukey test (P<0.05, except where otherwise noted).

SE can be a problem for broilers that do not yet have a fully matured immune system, as they cannot completely control the infection. Because of this, most of the responses improvements found in this study were found up to 14 days. Therefore, β-glucan supplements can help broilers achieve an earlier and faster innate immune activation and response, reducing/minimizing pathogen-caused damage and, consequently, performance losses. This type of response is particularly important for animals in the early stages of development and reproduction, or under periods of stress and environmental challenges, acting as a prophylactic and increasing animal resistance, thus minimizing further damage.

Many other different studies have proved the efficiency of ImmunoWall® in reducing contamination of pathogens in poultry and eggs (HOFACRE et al., 2017; FERREIRA et al., 2014), mortality and in improving productive performance (BONATO et al., 2016; RIVERA et al., 2018; KOIYAMA et al., 2018), mainly when challenged. There are no food additives that can overcome management, sanitation, vaccination, nutrition, or water quality problems, among others; additives are tools which can help prevent and control these problems. We understand that intensive animal production is a highly challenging environment, thus strengthening animals’ immune systems and maintaining intestinal microbiota may be one of the keys to better productivity.

Bibliography

Beirão B. C. B. et al. Yeast cell wall immunomodulatory and intestinal integrity effects on broilers challenged with Salmonella Enteritidis. In: 2018 PSA Annual Meeting. San Antonio-Texas, USA. Proceedings…. 2018.

Bonato et al. Desempenho de frangos de corte alimentados com mananoligossacarídeos, parede celular de levedura e nucleotídeos de diferentes fontes. In: Conferência FACTA 2016 de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas, Atibaia. Proceedings….2016.

Dalloul, R. A., H. S. Lillihoj. Poultry coccidiosis: recent developments in control measures and vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines, v. 5, p.143-163, 2006.

Ferreira, A.J.P. et al. Uso da associação de levedura e fonte de nucleotídeos na redução da colonização entérica por Salmonella Hiedelberg em frangos. In: Conferência FACTA 2014 de Ciência e Tecnologia Avícolas, Atibaia. Proceedings…. 2014.

Hofacre, C., et al. Use of a yeast cell wall product in commercial layer feed to reduce S.E. colonization. Proceedings of 66th Western Poultry Disease Conference, March 2017, Sacramento, CA, p. 76-78, 2017.

Koiyama, et al. Effect of yeast cell wall supplementation in laying hen feed on economic viability, egg production, and egg quality. The Journal of Applied Poultry Research, v. 27 (1), p. 116–123, 2018.

Lee, H. K., A. Iwasaki. Innate control of adaptive immunity: dendritic cells and beyond. Semin. Immunol., n. 19, p.48-55, 2007.

Petravić-Tominac, V. et al. Biological effects of yeast β-glucans. Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus, n. 75, v. 4, 2010.

Rivera et al. Yeast cell wall and hydrolyzed yeast as a source of nucleotides effects on immunity, gut integrity and performance of broilers. In: 2018 International Poultry Scientific Forum. Atlanta-GA, USA. Proceedings…. p. 49, 2018.

Posted in 06 January of 2022